AGI and The Efficient Compute Frontier

Quick Thoughts On When AI Value Will Be Accrued

Introduction

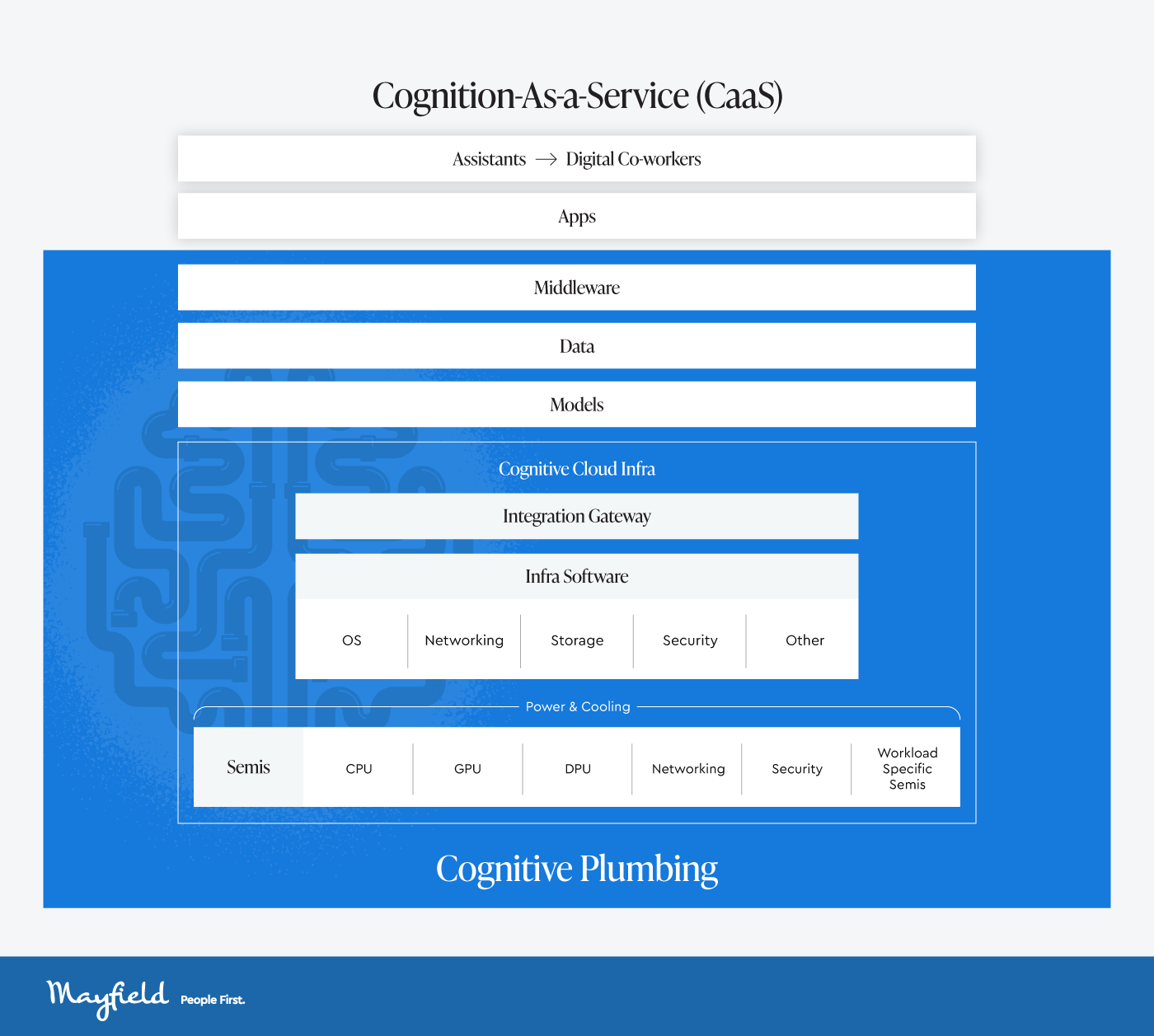

Mayfield Fund recently broke down the AI landscape into two frontiers: Cognition-As-a-Service (CaaS) and Cognitive Plumbing, the latter of which has recently taken off in terms of market cap, as realized through public market data.

However, that begs the question, when will CaaS actually begin to take off? In a past article, I covered the flipside of AI’s 600B question, where current pockets of value will be accrued in 3rd derivatives of AI CapEx buildout. In this article, I’ll talk about when it makes sense to finally see CaaS services cross the barrier-to-independence, which will be industry-dependent.

A Framework

CaaS Differentiation

To cover where CaaS applicability will be realized, we will first go over CaaS differentiation and product type.

CaaS is broken down into 3 categories, per Mayfield Fund:

Copilots (Assisted Intelligence; primarily provide suggestions and support)

Teammates (Collaborative Intelligence; works alongside humans, orchestrates)

Agents (Autonomous Intelligence; independent work)

Copilots

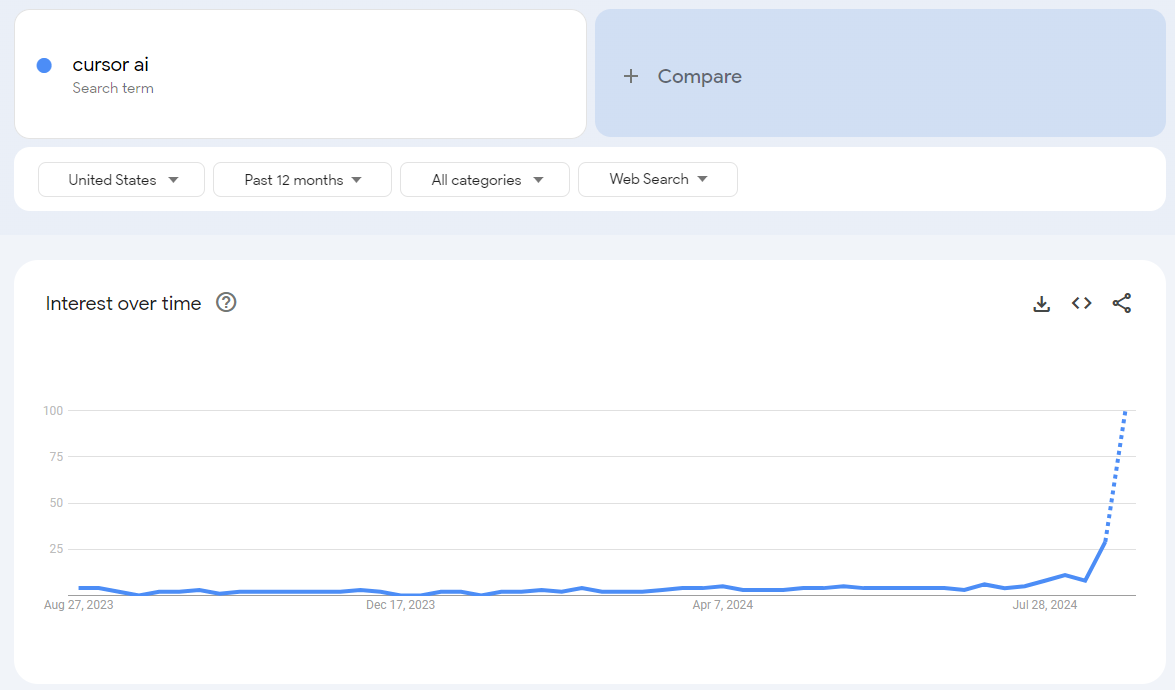

We’ve already seen the use case and popularity of AI copilots—a recent survey from the pragmatic engineer (n = 211) showed that around 71% of engineers had tried GitHub Copilot, and Cursor AI, a text-native code editor integrating natively with VSCode that recently had its “ChatGPT moment.”

In fact, The CEO of AWS, Matt Garman, made a bold prediction last month:

“If you go forward 24 months from now, or some amount of time — I can’t exactly predict where it is — it’s possible that most developers are not coding,”

Copilots have given us the first glimpse into the possibility of the future, boosting worker productivity greatly in frontier industries.

Teammates

AI Teammates are less prevalent but far more exciting—demos for projects like Devin have blown up on the internet, and VC funding has poured into AI Teammates. Projects like NeuBird’s Hawkeye, which generates full-stack solutions to IT telemetry data show promise in freeing up workloads for skilled individuals, allowing more time to be spent on AI-human collaboration and more high-stake problem-solving.

Agents

Though the line between Agents and Teammates is often blurred, high-stakes AI Agents often have access to important data-centric workstreams and typically have a much higher bar to approval. Early agents for the most popular use cases have succeeded in initial approval (e.g. self-driving cars), however, more niche use cases have yet to see widespread success.

Value Accrued

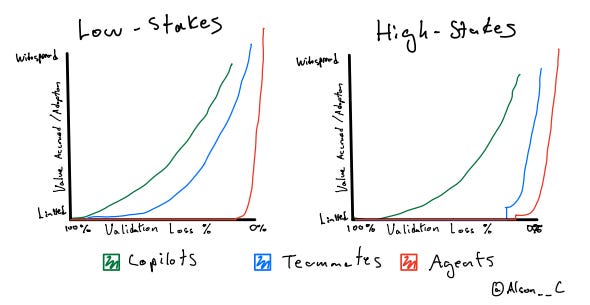

Thus, AI realization can be broken down into two categories: validation loss required and CaaS type, which can be further broken down between Low-Stakes and High Stakes.

Though the easiest way to differentiate between Low-Stakes and High-Stakes is by considering lives at risk to the Teammate/Agent in mind, an easy way to extrapolate this to business models is through contracts: the sales cycle of High-Stake industries are typically drawn out, and much longer (think DefenseTech or Healthcare IT), where there is usually significant lobbying involved as well.

To illustrate, I imagine a two-axis graph illustrating the relationship between value accrued and validation loss % required as follows (excuse my poor handwriting):

Here, considering low-stakes Copilots & Teammate models where all other features (UI, integrations, usability) ceteris paribus, the value accrued will follow a pretty obvious pattern: value accrued and adoption will depend mostly on dependability and validation loss %.

And this makes sense: the cost of a false positive for low-stakes tools (coding co-pilots, AI outbound sales assistants, or even AI legal assistants) is relatively low—unless pushed to prod, a mistaken coding co-pilot will probably rear its head during code review and can be easily fixed by a capable engineer; a misguided AI outbound sales assistant might email the wrong person or kill a lead, but will still be far from damaging the survivability of a venture; and an AI legal assistant will probably be fact-checked by a partner before being brought to court.

However, as the stakes start to become higher I expect the graph to resemble more of a step function. Teammates will only be trusted once a certain validation threshold is passed, and initial adoption is surpassed.

The most obvious industry that comes to mind is DefenseTech. Imagine an AI Special Tactics Officer who helps special operations teams determine where to deploy troops. It’ll probably take an extremely high (near 0%) validation error to deploy an AI tool when lives are at stake. Imagine if it goes wrong—significant geopolitical risks will be had! And worst of all, who do you blame?

And even worse is an AI agent. When do you give an AI agent the reigns to become fully independent? It takes significant investment and progress to even get initial approval (see self-driving cars, which have only just been starting to get approved in certain cities1).

Barrier-to-Independence

So when is this step?

The answer, as many things in life are, is complicated. Philosophers have debated the classical trolley problem for decades, whether the utilitarian solution (fewer deaths, e.g. comparing validation error to the error rate of humans) versus individual rights (do humans inherently have the right not to be put in harm’s way from robots?).

Though I’m not in the business of determining ethics, laws, or policy, for the sake of this exercise, we’ll consider this step to be the probability when a rule-bearing AI surpasses human ability +/- any expected variance.

In other words, we could calculate the step to be at the point when validation error < chance of human error. For example, the accident rate for traditional vehicles is 4.1 accidents per million miles. This means that the average self-driving car accident rate must be around the variance of the value. (Note—though still early, the reported accident rate for self-driving cars is around 9.1 per million miles driven, which makes their approval in SF an anomaly!)

Then, this begs the question: when will these results start to be realized? Introducing the efficient compute frontier:

The Efficient Compute Frontier

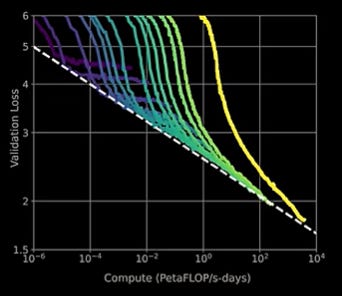

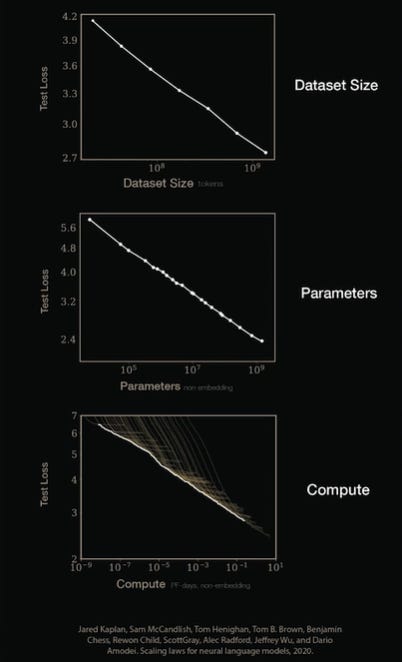

Even though recent larger models will generate a lower error rate, it will require a lot more compute, a trend that holds true as we seek a lower and lower error rate. Switching our axis to the logarithmic scale we notice a clear trend, where no model is able to cross a certain line (called the efficient compute frontier, noted in white dashes below).

Similarly, parameters and dataset size also follow the same trend when paired with validation loss, as shown below:

So is this trend due to a fundamental law of nature, or is this a result of the neural network-driven approach to AI development? Either way, seeing a model surpass these laws is most likely way out in the future (in AI years, so probably in the span of decades).

If I were to hypothesize, the path to full adoption of truly independent high-stakes AI Agents (e.g. AI WarMachines) will most likely be far out in development (due to extremely low test loss required), or run into a wall (lack of datasets/compute to power the training of extremely low test loss models). However, the development of less consequential AI agents is right around the corner, and businesses in these industries should plan for an AI-native world.

Thus, seeing value accrued in a way described by Leopold Aschenbrenner’s Situational Awareness is probably more far out than he hypothesizes, but definitely within the realm of possibilities.

Regardless of where your company lies within the low-stakes/high-stakes index, this feels like a do-or-die moment for legacy enterprises, and oftentimes, that means dealing with the chance of overinvesting with the risk of underinvesting.

If you want to chat about all things AI, Vertical Software, or investing in general, I’m always available on LinkedIn or Twitter.

It took 17 months just for Waymo to go from a driverless pilot permit to select city approval